One bright morning, 125 years ago, the first joint-stock publishing company of India came into being. It was founded by Kandathil Varghese Mappillai at Kottayam, a small town in the princely state of Travancore, on March 14, 1888.The name Malayala Manorama popped up at a brainstorming session attended by the great poets of the time, Kerala Varma Valiyakoyithampuran and Vilvattathu Raghavan Nambiar. Malayalis all over the world took the poetic name to heart.

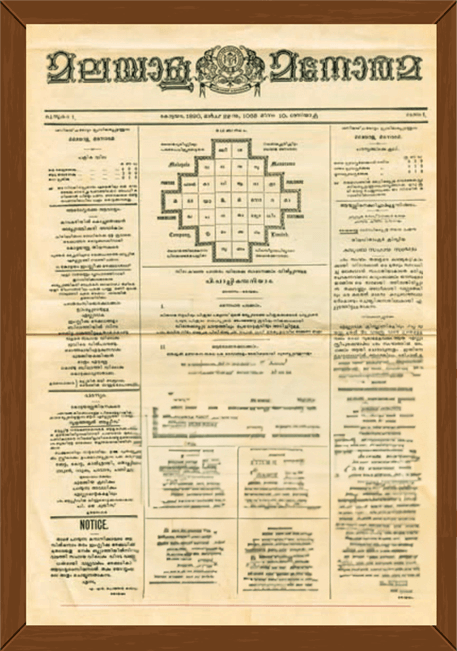

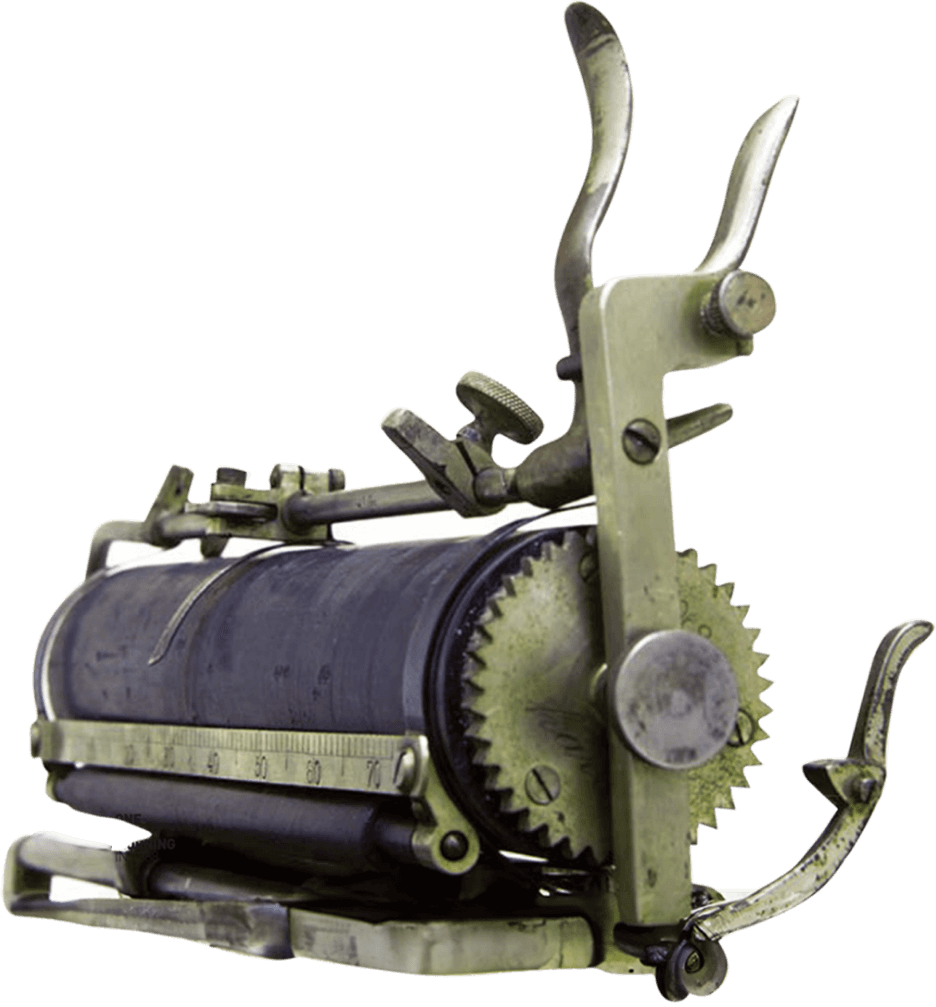

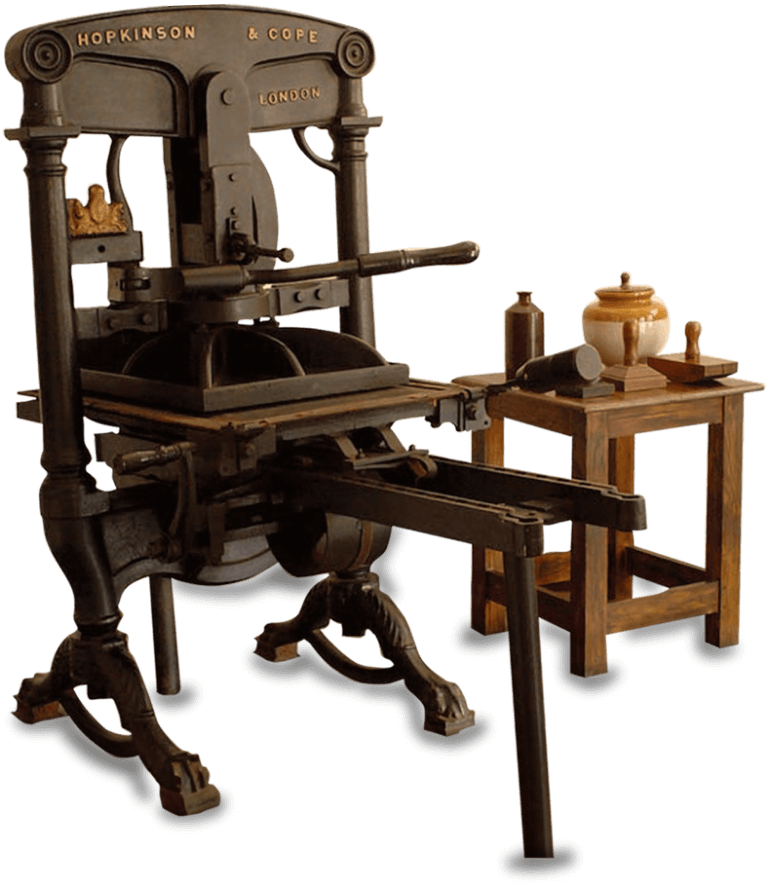

The company started with 100 shares of Rs 100 each. Some investors paid in four equal instalments. The first instalment went into buying a printing machine. It was a small treadle press, a Hopkinson & Cope, made in London. The pedal-powered press was installed in a vacant building, which would later become a cathedral. A local craftsman called Konthi Achari was hired to make quality Malayalam types for the imported press. It was a Herculean task. Being phonetic, the Malayalam script had 800 characters representing vowels, consonants, double-letters, triple-letters, diphthongs and various symbols and their different combinations. The typecasting delayed the birth of the paper by two years. (Kandathil Varghese Mappillai would later modify the script and reduce the number of types by half.) The first issue of the Malayala Manorama appeared on March 22, 1890, while Kottayam was hosting a highly popular cattle fair. It was a four-page weekly newspaper, published every Saturday.

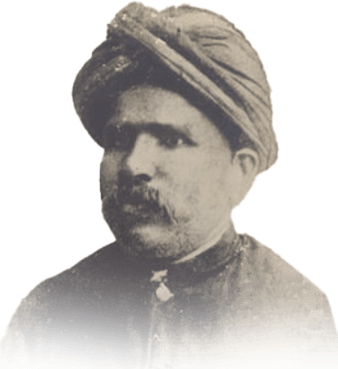

Kandathil Varghese

Mappilai

There were a few other newspapers around, mostly organs of Christian Churches. But Kandathil Varghese Mappillai decided to be different and secular.

As Kandathil Varghese Mappillai was a man of letters, there was an abundance of poetic outpouring and literary debates in Manorama. Manorama's heart was with the underdogs. Its very first editorial was a fervent plea for the education of the Pulayas, the untouchables who were not even allowed to walk on public roads. It was the voice of human dignity. The editor and his readers belonged to the landed gentry, which did not want the Pulayas to be educated, but the editor had the courage of conviction to swim against the tide. Thus began Manorama's fight against injustice and iniquity, one that would empower the people. Manorama grew exponentially. The weekly newspaper became a bi-weekly in 1901, a tri-weekly in 1918, and a daily in 1928. Today, Manorama is one of the world's largest daily newspapers, selling over 2 million copies a day. It is published from 18 centres: 11 in Kerala, five across the big Indian metros — Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, Bengaluru, and Mangaluru — and two abroad. The march goes on, winning hearts every step of the way.

Kandathil Varghese Mappillai was only 31 when he founded Malayala Manorama. An accomplished writer and an evolved thinker, he was very enterprising. As a 21-year-old, he had edited for almost a year, Kerala Mitram, a Malayalam newspaper from Kochi, run by Devji Bhimji, a Gujarati businessman. His mother despaired over his dangerous journey by canoe to Kochi from his home in Tiruvalla, which took him a whole week to complete.

With his editorials on human rights and greater powers to the Legislature, he ignited many a political debate. And, he spent reams on literature, throwing the pages of Manorama open to the finest poets and writers. He nurtured new talent. Soon after its birth, Manorama triggered a war over alliteration. It was the fiercest literary debate in the history of Malayalam. The rival phalanxes were led by the great poet Kerala Varma and his renowned nephew Rajaraja Varma. Literature was intoxicating stuff those days. In 1891, Kandathil Varghese Mappillai formed a literary club, Bhashaposhini Sabha. It brought together the tallest poets and writers from Travancore and Cochin states and the British-ruled Malabar. Locking creative horns, they did away with the awkward angularities of dialects. It helped develop the language and break the barriers of caste. The Sabha held interesting literary contests. Once, the challenge was to churn out within five hours a verse drama of one hundred stanzas in four Acts. Poet Kunhikkuttan Thampuran did it in four hours. He simply dictated it. He was a wiz at instant poetry. An offshoot of the Sabha was the Bhashaposhini magazine, which Kandathil Varghese Mappillai launched in 1892. It remains the most respected literary journal in Malayalam. Poetry and publishing were not his only passions. He was passionate about human development. The social visionary inspired the building of several schools and libraries. Shortly before his untimely death at the age of 47, he did something unthinkable in hidebound Travancore: he established the first residential high school for girls at Thirumoolapuram, near Kottayam in 1904. The rustle of this can still be heard in the giant strides Malayali women are making. The 50 years from 1904 were eventful for Malayala Manorama — years of struggle and evolution, power and glory, repression and rebirth. A reluctant recruit was destined to steer Manorama during its rise, fall and revival. A fresh graduate from Madras Christian College, K.C. Mammen Mappillai was preparing for the Indian Civil Service examinations when his uncle Kandathil Varghese Mappillai summoned him to Kottayam. He made the young man settle for a teacher's job in Kottayam so that he could also help edit the paper. On the death of Kandathil Varghese Mappillai on July 6, 1904, K.C. Mammen Mappillai, 32, became its editor. The uncle had groomed the nephew well, and the latter proved a worthy successor.

Long before the very idea of quality policy became popular, K.C. Mammen Mappillai issued one. It was his last dictum. His son K.M. Cherian published it five days after Mammen Mappillai's death: "By God's grace, Manorama is in a position to create and garner a forceful public opinion. This may be used for good or bad. But we should consider it as a public trust bestowed upon us for the selfless service of humanity. "You will have no qualms about using Manorama as a sacred public trust or an institution God has trustingly bestowed upon us to be used without fear or favour from anyone. You should always work with this in mind. God has placed in our hands a mighty weapon. To use it for our personal, vindictive and vitriolic ends will be an unpardonable and immoral act injurious to the faith bestowed on us by a large number of people. God does not want that. Hence, our eternal vow should be to tirelessly work for the success of fairness, justice and morality." It remains a sacred, inviolable dictum for Malayala Manorama.

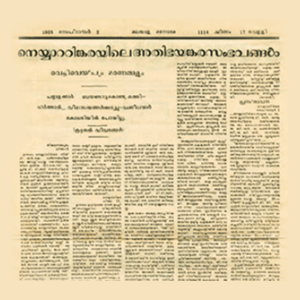

Show More...Malayala Manorama, September 2, 1938, on the Neyyatinkara incident For nine long years, Malayala Manorama remained in fetters, paying a heavy price for freedom of expression. The 1930s were tempestuous times for India's struggle for Independence. Malayala Manorama was at the forefront of the struggle in the princely state of Travancore.

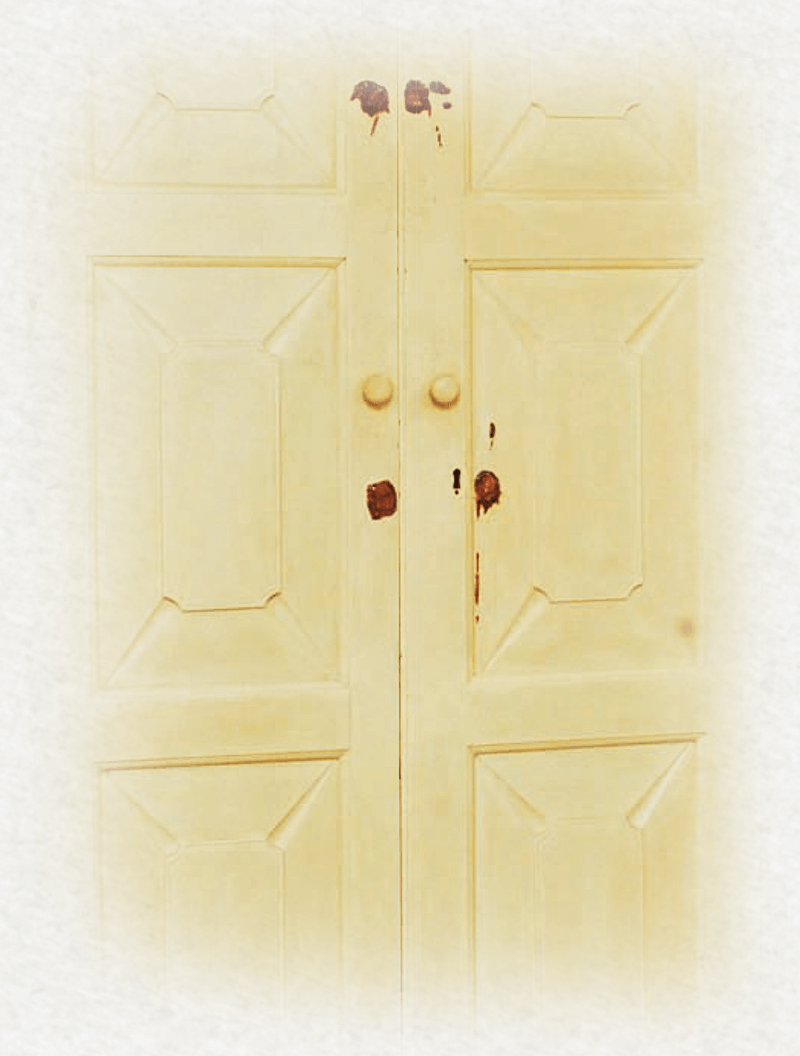

The paper was actively involved in the civil rights agitation, the formation of the Travancore State Congress and the historic campaign for responsible government, which was a campaign for self-rule. K.C. Mammen Mappillai's trenchant writings and public speeches invited the wrath of the all-powerful Diwan C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar, who was under the impression that Manorama was bankrolling the State Congress. He banned Manorama for its candid reporting on police firings and atrocities against people demanding democratic rights, at Neyyattinkara, on September 1, 1938. On September 10, 1938, armed police charged into the Manorama office at Kottayam and sealed its doors. The day Manorama was banned was the saddest in the life of K.C. Mammen Mappillai. Later, he was arrested and all his property confiscated. The Diwan was out to crush Manorama, and the civil liberties it espoused and the Press freedom it championed. For nine years, freedom of speech was in a comatose state. After India won freedom on August 15, 1947, the Diwan had to flee Travancore, having failed in his strategies to keep the princely state out of the Indian Union. On November 29, 1947, there was more reason to celebrate. Malayala Manorama was back. It was a glorious rebirth.

From travancore to national honours Even as Malayala Manorama was struggling to break out of its nine-year-long ban, a 50-year-old former professor came forward to strengthen K.C. Mammen Mappillai's ageing shoulders. It was his eldest son, K.M. Cherian. He joined his father as managing editor. It was Cherian who paved the way for Manorama's magnificent comeback. On K.C. Mammen Mappillai's demise, K.M. Cherian took over as chief editor in 1954. His immediate goal was the emotional integration of the people of Travancore, Cochin and Malabar, which combined to form the state of Kerala. He won acclaim for the admirable effort. He cherished lofty ideals and kept his father's last dictum close to his heart. But it was a struggle running the impecunious institution. And, there was a severe challenge from militant trade unionists. K.M. Cherian had immense faith in his employees. "If you don't want this institution to survive, I also don't want it," he told them. They rallied around him. Under his inspiring leadership, Manorama steadily gained strength and launched an edition from Kozhikode in 1966. K.M. Cherian also started a few other successful publications. The circulation of the newspaper soared from 30,000 to 3,00,000, and that of Manorama Weekly, which he had revived in 1956, rose to 3,29,000. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, while visiting an allied concern, remarked: "I shall confess that part of the reason which made me agree [to the visit] was also the fine record of Mr KM Cherian and his family in every business they have undertaken."

KM Cheriyan

K.M. Cherian was chairman of Press Trust of India and president of the Indian Newspaper Society. He received several national honours, including the Padma Shri and the Padma Bhushan. He died on March 14, 1973. If Kandathil Varghese Mappillai conceived Manorama and K.C. Mammen Mappillai moulded its character, K.M. Cherian breathed new life into it, and he won it national glory.

It was by a quirk of fate that the maker of modern Manorama, K.M. Mathew, joined the company. He went on to become a doyen of Indian journalism. His life was full of twists of fate. As a young man, he witnessed the sudden collapse of his father's business empire and subsequent imprisonment, courtesy of the wrath of Diwan Sir C.P. Ramaswamy Aiyar. Mathew was also a witness to the closure of Manorama and the nine-year struggle to reopen it. Mathew joined Manorama after working for more than a decade as a coffee plantation manager in Chickmagalur and as an entrepreneur in Mumbai. His eldest brother, K.M. Cherian, was running the revived newspaper with the blessings of their father, K.C. Mammen Mappillai. Cherian's financial resources were meagre, and the challenges manifold. That the paper came out every morning was a miracle. On the death of his father, Cherian became Chief Editor and needed an able lieutenant. He turned to Mathew with the consent of the entire family. Bowing to their wishes, Mathew wound up his business in Mumbai and joined Manorama in Kottayam as Managing Editor and General Manager in 1954. As Mathew later recalled, he saw on that day a world of potential for the paper. A world that made the 37-year-old's heart race. In 1954, Manorama had a circulation of 28,666 copies a day. Far from being the best-selling Malayalam paper, it stood fifth even in Kottayam. Undaunted, Mathew helped Cherian infuse new energy into the paper and make it fly high on the wings of innovation. He became Chief Editor on March 14, 1973, on the death of Cherian. The circulation of Manorama had touched the magic figure of 100,000 copies a day in 1961. Thirty-seven years later, in 1998, it became the first newspaper in India to sell one million copies a day. It crossed another milestone—1.5 million copies—in 2006, and added 100,000 copies the following year. That was music to Mathew's ears. "This is one of the most enchanting moments of my life," he said. A paper that had suffered nine years of forced closure, and after reopening had teetered on the brink of being sold off in distress, had touched 1.6 million copies! He died a contented man, at the age of 93, on the morning of August 1, 2010. By then, the circulation of Manorama had crossed 1.8 million copies a day. The paper from small-town Kottayam had established editions in 17 cities in India and abroad. The Malayala Manorama Company had grown into a colossal media conglomerate, with four dozen publications in five languages, and a strong presence in the electronic media. Manorama Weekly, Bhashaposhini, Vanitha, The Week, Balarama and several other magazines from the group had become best-selling publications in India. Manorama News channel, Manorama Music, Radio Mango and Manorama Online had raced to top spots in the electronic media. Mathew had a vision for Manorama. He knew the paper could progress only through innovation and professionalism. He attended professional courses abroad, brought the brightest minds in the field as consultants and organised workshops for newspapers in Kerala. His sustained efforts gave a vibrant new life to Malayalam journalism. He knew the pulse of the people, and his heart beat for his fellow beings. He made Manorama synonymous with social responsibility. The victims of earthquakes in Maharashtra and Gujarat felt his compassionate touch. So, too, did Indians fleeing the Iraq-occupied Kuwait. Mathew was chairman of Press Trust of India and Audit Bureau of Circulations, president of Indian Newspaper Society, and founder-trustee of Press Institute of India. He received several awards, including the B.D. Goenka Award and the Padma Bhushan. He wrote a touching book on his wife, Annamma, a year after her death. It was followed by his autobiography, Ettamathe Mothiram (The Eighth Ring), a few years before his death. His mind was like a steady flame, rooted in strong professional values. It did not sputter in times of distress, nor leap in exultation over achievements. He was a man of equanimity who remained down-to-earth all his life.

Manorama's first printing machine,a Hopkinson & Cope from London, was a hardy hand press. It cranked out 500 copies the day Manorama was born. It never once failed the printer, and it still looks good. Not all machines of later vintage were that tame. They would act up once in a while. One day, the V belt of a Marinoni press snapped. Printing superintendent Raghavan held fort with a coir rope till a new belt arrived the following day. When the DC motors of a flat-bed rotary press sputtered, he ran the press with the diesel engine of a lorry. It helped that he was once a motor mechanic! Big newspaper companies kept a spare press for emergencies. Manorama did not have that luxury. Once, a printing expert from America visited Manorama in Kottayam. He took a look at the press on the ground floor and asked Chief Editor K.M. Cherian, "Where is your spare press?"

Cherian pointed his index finger upwards. The American thought that the spare press was located on the first floor. It was Cherian's way of saying that God would take care of the spare press! Manorama has come a long way since then. It is a weird world out there — a world of LANS, WANS, BINUSCANS, PDFs, SAN boxes, and XML— compliant systems. It has always relied on appropriate technology. In 1981, it graduated from letterpress printing to offset printing by installing French-made Creusot Loire Gazette presses in Kottayam.

New offset presses cost the earth. So Manorama did something unbelievable: buying spare parts, it converted two old letter presses into full-fledged offset presses. Manorama embraced photo-composing the same year, phasing out mechanical Monotype and Linotype hot-metal typesetters. Not long afterwards, it installed telephoto transmitters and digital scanners for colour separation. The use of facsimile technology in 1986 eliminated duplication of page-making at different printing centres. Manorama was the first to use a flat-bed facsimile system in India. Manorama was the first in the country to use an automated mailroom system for counting and packing newspaper bundles. Journalists in Manorama took a giant technological leap in 1996. They had never used typewriters; yet they switched over from handwriting to computers and page-making in one fluid motion. They were the first journalists in the regional language press in India to use computers to make pages. The entire software for the editorial system was developed indigenously in Pune. Manorama has many other firsts in India to its credit: the first to use computers for making multipage advertisement dummy; the first to install a computer-to-plate output device, eliminating film; the first to publish an e-paper; and the first to use MPEG4 technology and tapeless cameras for television. Fascinating firsts... not to boast, but to make lasting impressions.